Texts

A Westphalian Postwar Modernist

Bernhard Gewers – A Westphalian Postwar Modernist

By Carina Plath

A platform with a multitude of transparent tubes that can be filled with different coloured liquids (Großes Farb-Licht-Wasserspiel (Modell), 1976), a bronze Madonna with a child standing sideways, surrounded by a ring containing uncut rock crystals (Madonna with World Wheel, 1952), a slab with a dystopian-looking city map with destroyed buildings (Die Inbesitznahme der Erde durch den Menschen, 1969), metal choir barriers for the abbey church in Gerleve (1972) and abstract concrete reliefs (1984): All these are works created by the sculptor Bernhard Gewers between the 1950s and 1980s, showing the extreme range of this gifted craftsman and artist.

From today‘s perspective, Gewers‘ artistic works contain sensual and physical qualities that seem largely lost in our everyday lives. His work is diverse, individual and also typical of his time; Gewers is just as much an artist characteristic of the post-war period as he was always able to find individual solutions with the help of his craftsmanship, his broad knowledge of art history and his attachment to the landscape and artistic tradition of his adopted home of Hagen am Teutoburger Wald.

If you visit his cottage and above all his workshop, where much has remained unchanged after his death, you will recognise this from the fully filled glass cabinets that collect models, found objects from nature, test castings and materials. Behind numerous pieces of historical furniture, one finds parts of Gothic and Renaissance stone sculptures from old buildings - here a pinnacle, there a small Baroque angel. Stowed away on the ledge above: early heads and attempts at realistic art, hanging from the ceiling beam is the scythe used to mow the meadows by hand.

This workshop situation and the choice to move to the small town near the Teutoburg Forest are telling - even without having known the person Bernhard Gewers. The artist is a child of his time: from his experiences at the front in the Second World War, which is not spoken of, to the time of departure with his apprenticeship and master‘s examination as a stone and wood sculptor at the Werkkunstschule Münster, the study of architecture at the TU Darmstadt, finally the study of art at the Academy in Stuttgart, which he completed as a master student in 1953, to his marriage and founding of a family with Ilse Strauss, also a sculptor, in 1959, and the birth of their three sons. Gewers is a bourgeois and solid artist; his generation is characterised by consolidation after the devastating war experiences, growing up in the rubble landscapes and the scarcity of means that existed at first. Emotionally and psychologically, for many this also meant repressed traumas, the continuation of patriarchal structures and often reserved to indifferent fatherhood. The generation of war children was scarred, but after the war they felt they could fall back on the craft traditions and masteries of their grandfathers‘ generation and make a virtue out of necessity. Simple materials and means stood for this strategy as much as they followed the apparent necessity to start again with „zero hour“. From today‘s perspective, this did not exist either socially, politically or artistically; the continuities existed in the offices and positions as well as in society as a whole. Figures such as Gewers‘ teacher in Darmstadt, Ernst Neufert, the Bauhaus student and famous author of the standard work Bauentwurfslehre (1939), who was supported by Albert Speer during the Second World War as Reich Commissioner for Building Standardisation and was responsible, among other things, for the rationalisation of industrial building, and who was appointed professor at the TU Darmstadt after 1945, where he continued the Bauhaus teachings, are paradigmatic of the careers of the time. Due to the many executives and scientists who were killed, expelled or discarded as Nazis, the denazified professors as well as the women educated in the 1920s were initially the ones who took over the many empty positions at universities and museums. But it was not only the leading figures that Gewers worked on - alongside colleagues such as Otto Herbert Hajek, with whom he studied together in Stuttgart, there were also everyday figures such as the Academy‘s caretaker, whom the artist depicted in his early portrait Pelzer (1951). The realism practised on him, reminiscent today of sculptures by the younger Stephan Balkenhol, was the young artist‘s first and direct approach at the time, and he continued to orientate and train himself in his practice.

The post-war art world is characterised by open discussions on art that parallel and mirror the formation and life of the democratic constitution of the Federal Republic of Germany. The bitter dispute between the art historian Hans Sedlmayr and the artist Willi Baumeister at the famous Darmstadt Talks of 1950 divided the artists into supporters of figuration and abstraction. A long-lasting dispute ensued, which also had harsh personal consequences for some, such as the then president of the Berlin University of the Arts, Karl Hofer, who saw himself denounced as a figurative painter and isolated from the prevailing discourse. Dominant were the leading critics Werner Haftmann and Will Grohmann, advocates of an anti-National Socialist, progressive abstract modernism, who were also close friends with international critics such as the influential Briton Herbert Read. The triumphal march of the British artists, first Henry Moore, later the representatives of the so-called „Geometry of Fear“ (Read) Lynn Chadwick, Reg Butler, Kenneth Armitage and Edoardo Paolozzi was financially supported by the British Council and used for the moral education of the German population. Arnold Bode showed them prominently at the first two documenta shows in Kassel in 1955 and 1959.

The German sculptors admired Moore, who also visited some of them in their studios in Germany, but were quite independent. Among the most important were Hans Uhlmann and Karl Hartung, and among the painters Willi Baumeister, Emil Schumacher and Ernst Wilhelm Nay, who found their own ways of formulating a moderate abstract modernism that continued the abstraction of the 1920s.

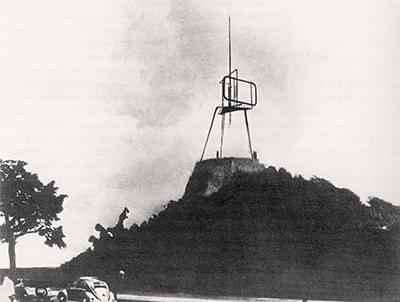

Spectacular competitions such as the one for the „Monument to the Unknown Political Prisoner“ (1952/53) for Berlin certainly did not pass Gewers by. Naum Gabo, Barbara Hepworth and Antoine Pevsner, among others, but also Alexander Calder and Max Bill took part in the competition for a large monument in Berlin, which offered prize money of 50,000 DM, and the number of more than 3,000 applicants shows the „who‘s who“ of international art of the 1950s. The winner was a highly controversial antenna- and watchtower-like sculpture by the British sculptor Reg Butler, which rekindled the general public‘s great hostility towards abstract, „non-human“ art in the broad discussion in the press.

In his cage-like sculpture Trapped in Space, (c. 1956) Gewers reflects themes of the many designs in the competition, such as sculpture‘s current preoccupation with the dissolution of mass in favour of circumscribed space. The mixture of bronze and steel on the unhewn stone base reflects as much the sculptors‘ preoccupation with the contemporary materials of steel and iron, previously unworthy of art, as it does the imprisonment and transparency of the grid-like cube with the imprisoned figures. New concepts of space, in which sculpture could be characterised by the free-standing void, had previously been seen in Moore, Butler and Hepworth. It is very clear from Gewers‘ sculptures that he was aware of and engaged in the current discussions of the time.

The West German art scene was very small at the time, important centres such as the Rhineland with the galleries in Cologne like Rudolf Zwirner (first in Essen), or Düsseldorf (Alfred Schmela), but also the smaller Münster in Westphalia with the Clasing Gallery were places where people met for openings and artists‘ festivals and where institutions like the art associations slowly began to show contemporary art. Gewers exhibited at the legendary junger westen in the Kunsthalle Recklinghausen in 1957 under Thomas Grochowiak, participated in artist groups such as Neue Gruppe Münster 60 (with Pan Walther, Hilm Böckelmann, Ernst van Briel, Albert Stuwe, among others), which produced exhibitions (Galerie Clasing 1960) as well as editions (portfolios from 1961 and 1964), and was a member of the Schanze in Münster from 1965, which united the Westphalian artists of his generation.

In addition to Gewers‘ diverse education, his Catholic upbringing in Westphalia shaped his work and became increasingly important in later years. Questioned by the events of the war and the behaviour of the churches under National Socialism, the Christian congregations were nevertheless revived as communities in the post-war period, to which the new awakening of architecture, evident in advanced church buildings, made a decisive contribution. In addition, Gewers, like many artists of his generation, found new clients here. Christian themes and ecclesiastical commissions determined a large number of his activities and led to the most beautiful results. The Madonnas and the Calvary, for example, are early examples of how intensively the sculptor dealt with these themes.

Similar to the early work of Henry Moore, who created a large number of Madonnas and took up Celtic models in his crosses, Gewers also devoted himself to these themes as a sculptor of his time. In his work, the Calvary is a flat base with crosses rising vertically all the higher. The central cross with the figure of Christ is at the same time surrounded by a disc, inaccessible to the lance thrust of the Roman horseman waiting below and removed to the higher realm.

The overlong ladders standing on either side, as well as the other two crosses with crucified figures turned into profile on the right and left, have formally become frameworks that all the more strongly nobilise the central figure. Such a sculptural solution was not found quickly, but was worked out in numerous drawings and smaller models. This is shown by the earlier version, in which he worked with a simpler, less stylised and more concentrated accumulation of figures and crosses. The clear structure translates into a meaningful order of God in which Christ is the dominant element and becomes the ruler precisely in death as the Redeemer. A further byway of the development of this sculpture is shown by the numerous sheets of drawings and watercolours with constellations of forest-like thickets rising vertically from a horizontal plane to towering industrial parts and finally lances and crosses. Through formal analogies, the possibilities of life structures of horizontal and vertical, of rootedness and detachment, of static and movement, of sun and ray alternate and enrich in a development perpetuated by the artist.

Gewers has found convincing formal solutions for other objects of the religious context. In the Small Monstrance for the St. Franziskus Hospital in Münster (1972), he emphasises transparency and the view of the consecrated host through the rich use of rock crystals in uncut and cut form. It serves entirely as a vessel and yet, in the crystalline and golden setting, is at once dignified and an image of divine providence and purity. Other ecclesiastical tasks are concrete glass windows, gravestones, baptismal fonts, altars and church doors, for which Gewers invents and realises variations that are as modern as they are individual.

From the 1950s to the 1980s, the Art in Construction Act, which stipulated that a percentage of the construction costs of federal buildings be invested in art, gave artists new tasks. There was also the notion that art could serve an educational and healing purpose through play. Especially the commissions for fountains in the pedestrian zones of the newly rebuilt cities became places of communication and play.

Gewers also took part in some competitions for art on buildings and fountains in public squares; even if not all the competitions were won, the beautiful models with which Gewers competed remained. The Water Games, Trombone Fountain and Music Machine are wonderful designs for fountain sculptures moved by water, which unfortunately were not executed. The artist designed multipart sculpture fields in imitation of the growth of plants, which, through their diversity and liveliness as well as their patina of verdigris, added to the tactility of the surface.

Towards the end of the 1960s, a lot changed, not only politically, due to the 1968 student revolution. The first moon landing, the threat of the Vietnam War, the apparent limits to growth and new discoveries in physics influenced sculptors at this time. Gewers‘ expression also changed. The landscapes are no longer romantic ones, but destroyed ones, permeated by technology, rutted, with wires and antennae and lookouts. Here, the machinic notion of architecture of a Le Corbusier meets the weathered, patina-ridden, wrinkled skin of an impaired earth, hinting at science fiction film sets like those of Star Wars. The Occupation of the Earth by Man (1969), an application for a free sculpture on the Münster television tower, shows how Gewers approaches the theme of alienation and mechanisation. The skyscrapers of a cityscape, at first hinted at in a small sketch, give way to more abstracted antennae, cages, batteries and pillars shaped like stamps, occupying an area without human figures and on a platform which - held in suspension above a concrete block - dynamises the whole surrounding space. Gewers photographed this design in the typical manner of the time from below, in front of a cityscape of single-family houses, so that the drasticness of the design is heightened in relation to its small-town surroundings. Added to this is the sculptor‘s technical skill in giving the bronze surfaces and points a handmade, special patina that reinforces the drama of the elements that appear weathered or burnt.

„Cosmic landscapes“ is what Gewers calls his shallow reliefs, which are characterised by rays, sunlight collectors and accumulator-like apparatuses. The large plaster model with its furrows and structures traces its origins to the dystopian 1970s. Comparable to the sculptures of an Edoardo Paolozzi from the late 1950s, in which he integrated imprints of machine parts into his bronze surfaces of figures, the surface of these machine-like installations is as technoid as it is apocalyptic.

From the 1980s onwards, the sculptor exploits the new technical possibilities of concrete casting in the Concrete Glass Windows and the Reliefs (1984), in which he superimposes concrete grids in several layers to create a vegetal, overgrown structure that allows the light to shine through in a refracted manner. Again, Gewer‘s attention to detail and the great artistic care with which he approaches the materials is evident. In his cottage are the old models from whom he borrows the techniques - the Westphalian stone sculptors such as the Brabenders and Johann Wilhelm Gröninger, and in front of the door is the mossy sculpture that becomes more and more beautiful with time. Finally, the gravestones he designed and carved for friends and clients are found in the cemeteries. In the late period, ecclesiastical commissions took up even more space and so Gewers also left his mark on his immediate surroundings with his reliefs, building decorations and sculptures.

If you drive through Hagen, you will see St. Martin on the monumental marble relief at the height of the church, as he gently places his warm cloak around the shoulders of the beggar. This almost classicistic work by Gewers can stand for his late work, in which light and rounded forms appear and once again give his artistic expression a different character. The simple remains, just as the group of crosses in the cemetery gets its meaning from the simple grouping that makes the crosses into a family.

May it be Westphalian simplicity, may it be ascetic from the experience of lack or simply modest and thorough, Bernhard Gewers has combined the typical of the time and the individual in his sculptures in a way through which they point beyond the merely regional and merely individual. What remains are works that not only speak to his family, the community and the locality, but also provide an insight into a detailed, diverse, technically and artistically sophisticated oeuvre of a German artist of the post-war modern era. In this, his work meets that of the long disregarded medieval and Renaissance artists from Cleve, Soest and Münster, whom he admired so much.

Carina Plath

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

|

|

|

||

|

||